New research uncovers a gene mutation in bed bugs linked to pesticide resistance, echoing traits found in German cockroaches.

A global bed bug resurgence is raising new concerns — and new questions. Once nearly eradicated in the 1950s with the pesticide DDT (now banned), bed bugs have rebounded worldwide, showing troubling resistance to a range of insecticides.

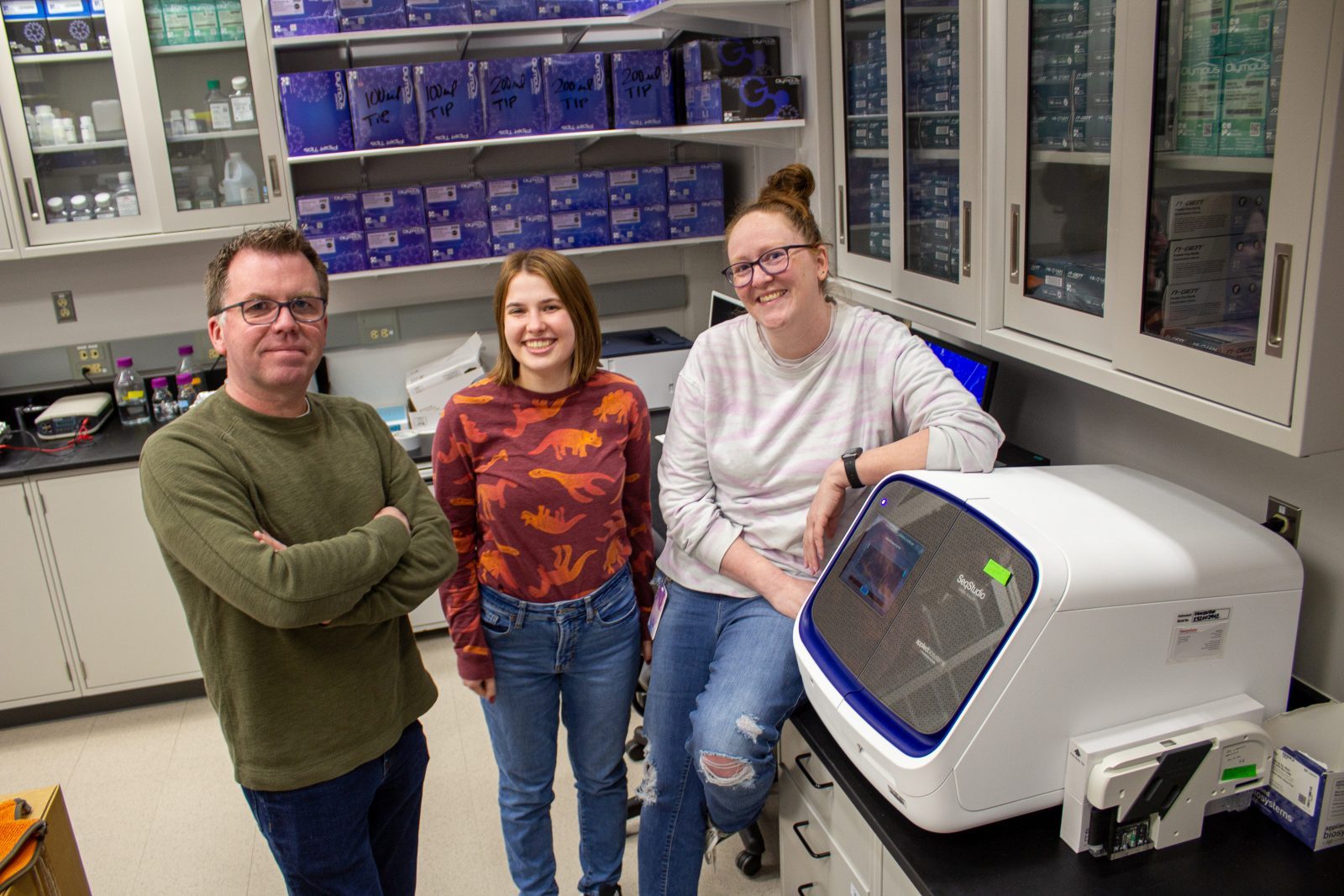

Now, a study published in the Journal of Medical Entomology has identified a potential reason why. Led by urban entomologist Dr. Warren Booth of Virginia Tech, the research team discovered a gene mutation in bed bugs that may be responsible for this growing resistance.

What started as a training exercise in molecular techniques for graduate student Camille Block turned into a pivotal discovery.

“It was purely a fishing expedition,” said Booth, Associate Professor of Urban Entomology at Virginia Tech’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “But I had a good idea where to cast the line.”

Booth, who specializes in urban pests, was already familiar with a mutation in the nervous systems of German cockroaches and whiteflies that grants them resistance to certain insecticides. He suspected bed bugs might share the same adaptation.

To test the theory, Block analyzed one bed bug from each of 134 unique populations collected across North America between 2008 and 2022. Two of those samples — from separate populations — revealed the mutation.

“It was literally my last 24 samples,” said Block, a student affiliate of the Invasive Species Collaborative. “I’d never done any molecular work before, so gaining these skills was super important.”

Thanks to the genetic uniformity caused by inbreeding in bed bug populations, a single sample often reflects an entire colony. Still, to confirm the findings, the team tested multiple bugs from the two mutated populations — and every specimen showed the same gene mutation.

“They were fixed for these mutations,” Booth said. “And it’s the same mutation found in German cockroaches.”

The gene in question, known as Rdl, is linked to resistance against dieldrin, a banned pesticide. Interestingly, dieldrin shares its mode of action with fipronil, a chemical still in use today for treating fleas on pets — though not approved for bed bug control.

Booth theorizes that bed bugs may be unintentionally exposed to fipronil when pets treated with the chemical share beds with their owners.

“We don’t know if this mutation is novel, if it popped up recently, or if it’s been around in bed bug populations for over 100 years,” Booth said.

To find out, his lab plans to search for the Rdl mutation in bed bug specimens from other regions — especially Europe — and from preserved samples in museum collections.

Booth’s team also recently became the first to sequence the full genome of the common bed bug, opening the door to deeper historical and evolutionary studies.

“Now that we have chromosome-level templates, we can take degraded fragments from museum specimens and reconstruct full genes and genomes,” Booth explained.

The research may also help pest control companies pinpoint where resistant bed bugs are thriving and how to fight them more effectively.

As for Block, the unexpected breakthrough has only deepened her interest in urban pest evolution.

“I love evolution. I think it’s fascinating,” she said. “People connect with urban species like bed bugs because they’ve likely encountered them. It makes the science more real.”

Dr. Lindsay Miles, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Entomology, also contributed to the research.

Source: Virginia Tech